- Home

- Gooch, Patrick

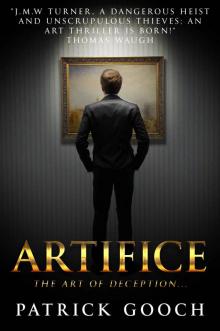

Artifice

Artifice Read online

ARTIFICE

By Patrick Gooch

Patrick Gooch © 2017

Patrick Gooch has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published by Endeavour Press Ltd in 2017.

Artifice

A Skilful or artful contrivance,

a stratagem calculated to trick

or deceive others.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 42

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 45

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

If you enjoy Artifice check out Endeavour Press’s other books here: Endeavour Press - the UK’s leading independent publisher of digital books.

For weekly updates on our free and discounted eBooks sign up to our newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter and Goodreads.

Chapter 1

It was to be a simple service in the village church.

No obituary notices had been posted in the local or national newspapers. Given his age, it was doubtful what few acquaintances remained, would be inclined to venture this far to pay their respects. Only family, and perhaps curious neighbours, would be the likely mourners.

However, when the cortège arrived and we made our way to the front pew, I was suddenly aware the church was not only full, many were standing in the side aisles.

After the interment, as people shuffled by muttering kind words and condolences, my mother invited them to enjoy refreshment at the house.

Fortunately, the caterers were able to satisfy the increased numbers; and for much of the afternoon the downstairs rooms were filled with people eating, drinking, and no doubt reminiscing about their association with the deceased.

Dutifully, I had circulated among them: the majority unknown to me. Not given to prolonged bouts of small talk, I eventually wandered into the garden and slumped down on a bench overlooking the lake.

It was the end of an era.

*

I was five years old when first taken to Mead Court. A large, secluded house set in ten acres of lawns, shrubberies, and woodland. A taxi from the railway station had whisked my mother and I through imposing gates, up a tree-lined drive, to a halt on a broad, gravelled forecourt. I recalled the massive entrance door swinging open, and an elderly man coming forward and hesitantly wrapping his arms around her.

Being a child, I was intimidated by his presence. Much of the time cowering behind my mother`s skirts, remaining obstinately silent despite his attempts to engage with me.

It was not until we were on the rear terrace and two dogs bounded up, did I slowly shed my timidity. They were my playmates for much of the afternoon.

Throughout the return journey the two Labradors were uppermost in my thoughts. `When can we go again?` I pestered my mother.

Another thought flitted through my mind.

On the occasional visits thereafter to Mead Court, my father never once came with us. Mother always declared his work came first. But was he so occupied when weekends were spent there?

Later, I discovered that their marriage had not been welcomed, causing enmity between the two men. Eventually, my father refused to accompany mother on her trips. The intervals between visits lengthened, and gradually petered out. Thus, my first encounter of Mead Court was, for my mother, a sort of reconciliation with Michael Johns – my maternal grandfather.

*

We lived in a house in the suburbs of London. A modest dwelling built in the nineteen thirties. Each day father, Richard Cleverden, would catch a train into the city, and in the evening return at precisely five forty five. In the summer months, before his evening meal, he would spend time tending his vegetable patch in the back garden and the roses at the front of the house shielded from the roadway by a low fence.

A man of habit. A man who became more and more set in his ways during the passing years. On Saturday mornings he would buy flowers for my mother and cigarettes for himself. Items mother requested were bought, listed on a scrap of paper, and presented as a bill to be deducted from the housekeeping. After lunch he would polish his shoes, select and brush a suit to wear for the coming week, and check his football pools coupon.

Like others in the avenue, regardless of the weather, on Sunday mornings he would wash the small, family car. Then he would offer us a brief trip into the countryside. Invariably, it would be to Box Hill or the North Downs, where we would look out the car windows for twenty minutes or so, then drive home for afternoon tea.

Older than mother, it was only to be expected he would age faster. But it seemed to accelerate when his health deteriorated. At fifty-eight he suffered a heart attack, passing away still seated at his desk in the bank.

After the tears had dried, mother found a job, a menial task that paid little. I often found her counting the coins in her purse, and we moved from the house into rented rooms.

As a child, it did not affect me overmuch. However, I later learned we led a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence – until the day footsteps were heard on the stairs. There was a hesitant knock. I saw the startled look on mother`s face when I opened the door.

I still remembered the words he spoke.

“I`m sorry it`s taken so long to find you,” murmured Grandpa Johns.

I would have been eight at the time. More aware of the world and the people around me. Yet, I still could not comprehend the reason for the fierce exchanges between father and daughter; the raised voices that accompanied his visits.

No longer uneasy in his presence, I came to enjoy his company. Nevertheless, I was angry on those occasions my mother was upset, and would stand by her side with clenched fists when harsh words were bandied between them.

It took several visits, before she seemingly agreed to his wishes.

At the time I did not comprehend all that was entailed. Until the few belongings we now possessed were boxed and taken off in a small van. Whereupon, we boarded a train to Dorset, and went to live at Grandpa Johns` house in Melbury Abbas, a hamlet on the outskirts of Shaftesbury.

*

M

y mother wandered onto the terrace, interrupting my thoughts.

“I knew I`d find you in your usual seat. People are about to leave, Alan. Will you stand beside me when they make their goodbyes?”

I exchanged a few words: a handshake, a cheek briefly kissed, as each of the departing guests hesitantly made his or her farewell. When the caterers began the task of returning the reception rooms to normal, my mother murmured. “I think I`ll go upstairs for a while. It`s been a tiring day. Would you mind keeping an eye on the activities down here?”

For the next hour I hovered as the tables were cleared of debris; glasses and plates stacked into containers; napkins and tablecloths dropped into large linen bags; and the carpets vacuumed clean. When the last of their vehicles had made its way down the drive, I poured myself a glass of wine and resumed my seat on the terrace, where the late afternoon sun conveyed a gentle warmth.

Putting the glass to my lips the thought came, this was a wine from the Navarra region of northern Spain - always a favourite of Grandpa Johns`. I smiled. I too had come to regard it with the same enthusiasm. Another of the many traits, idiosyncrasies, and occasional virtues, I had unthinkingly adopted under his influence.

What I had also not been aware of was his hand in guiding my education.

For the first few years at Mead Court I attended the King Alfred School in Shaftesbury. Each day, Grandpa`s aide and long-time companion, McKenna, would drive me into the town, and collect me when lessons came to an end. Very different from the walk to school in all weathers through the cluttered streets of London.

An even greater upheaval took place when I was thirteen.

I became a boarder at Marlborough College.

It took some time for the shock to ease. I was cast among strangers when allocated a quarter share of a room in Turner House. Far different from the spacious bedroom at Mead Court, to which I had become so readily accustomed.

The Turner building was up the Bath Road, a few minutes’ walk from the Inner Campus and the main buildings. Fees were never mentioned, and whatever I needed – clothing, books, sports equipment – simply appeared. I did not realise at the time that Grandpa Johns paid for everything, including a hefty donation to the Marlborough College Foundation, which may have helped secure my place at this prestigious seat of learning.

McKenna – he preferred to be called McKenna - would collect me and my trunk at half-term and end-of-term breaks to spend the vacations at Mead Court. While I was there grandfather would quiz me closely on my progress: who were my friends, and the subjects in which I was most interested.

Those I found the more enjoyable were English literature and art. I could draw and wield a paintbrush quite well. What also interested me were the artists. In particular, their ways of life, their individual qualities. On reflection, such interests may again have been shaped by my grandfather`s passion for works of art.

Mead Court had a wide frontage facing onto the forecourt, but it also had significant depth. Much of what was behind the facade was added when Grandpa Johns first took up residence. Not only had additional rooms been built, running the depth of the house was a long gallery.

Light flooded in through slightly tinted windows, which blocked the more harmful sun`s rays. On the opposite wall was an array of quite magnificent paintings. They would have been priceless if original works, for they depicted the æsthetic themes from the Renaissance, the Impressionist period, and French and Flemish paintings.

However, if one looked closely, on each frame below the title were the inscriptions: `in the style of`, `after`, `from the school of``, and , `copied from`, followed by the (names of celebrated artists. If originals, they would have fetched millions; but though carefully produced by an apprentice, or skilfully painted by an unknown artist, their value was markedly diminished.

I would often stroll through the gallery with Grandpa Johns, while he talked at length, often in German, about the paintings, or more correctly the original works and their creators. Small wonder that my appetite for the subject was fired at an early age. I had a ready tutor, a linguist from his years spent in Germany, and first-class copies of the pictures by noted artists.

However, there was one painting that had long captured my imagination.

It hung in Grandpa`s study.

As a small boy whenever we visited Mead Court, I would slip past the adults while they exchanged greetings, and make for the study. Shutting the door behind me I would gaze up at the framed canvas on the wall. Entranced by the jungle scene, I would sit in Grandpa`s chair and drink in the vibrant colours, the wild animals frozen in time as they stalked their prey. Totally absorbed, I was reluctant to join the others, despite their entreaties.

The painting was a copy of a work by the French artist, Henri Rousseau. Apparently, it was the second in the series of jungle scenes by the Parisian toll collector. Grandpa Johns declared it was closest to the original than any of the works he possessed. Most often he would come to fetch me and make the comment, `studying the Rousseau, my boy? I can see I shall have to leave it to you in my will.`

*

As the years passed my enjoyment of the painting never waned. Even when, at eighteen, I left Marlborough College and enrolled as a history of art student at the Courtauld Institute, and at University College London to read English. When travelling between the two schools of academia, the proximity of the Northern Line Underground suited me well.

I poured another glass of wine, savouring its rich depths of flavour.

It was at the Institute I met Sophie Linard. A dark-haired, attractive young woman from Cyprus. Although, plagued by a steady flow of admirers, she fended them off with ease, seeming to prefer my company to the tongue-tied, sycophantic followers. Probably, because I did not make much of the relationship, did not fawn over her, that sparked Sophie`s mild interest.

Perhaps, I had always been that way. I have had girlfriends, but was never given to the pangs of the lovelorn. I, invariably, loved the current enchantress; but when she found another, we parted without rancour. The world did not come close to an end.

While my friends appeared to move from one `light of their life` to the next in a seesaw of passionate highs and lows, I, on the other hand, sailed through this phase of my formative years with my emotions comfortably undisturbed.

At Courtaulds, liaisons lasted longer. For example, Penny, a fellow history of art student, and I lived together for eighteen months. She was attractive, lively-minded and not too demanding. I never thought about the future. Penny was there: the unstated presumption was she would be there tomorrow and, no doubt, the day after.

She was a year ahead of me. Suddenly she graduated, took her toaster, and kissed me goodbye. I was a little put out, but not distraught. Others came into my life leaving the same untroubled impression.

But the challenge was growing. How could I get Sophie into my bed? She would visit my flat – courtesy of Grandpa Johns – attend parties and join me for intimate dinners; but always left by eleven o`clock. At that hour a taxi would draw up and whisk her homewards.

After we graduated I was fortunate to land a job as an assistant editor at a publishing house. Or was it luck? Thinking back, I wondered if Grandpa Johns had also had a hand in easing my way into the journalistic world.

Sophie opted to continue her studies, taking a post-graduate course in paintings conservation. Now following different paths, we saw less and less of each other, and our trysts were few and far-between.

I grinned to myself, and indulged in more of Grandpa`s wine.

I raised my glass to him, wherever he was. Though I was pretty certain he would never have made it to Nirvana. Although I came to love him dearly, it slowly dawned on me he had been something of a rogue in his earlier days. Even in his dotage I occasionally had the feeling he was up to no good.

As a child and a teenager I had never thought to question people coming to the house late at night; the sound of heavy footsteps on tiled floors; or when I was suddenly barred fro

m Grandpa`s study. Then, there were the times I noticed new works hanging in the gallery, or those which had long been on display, disappearing.

There were also times when the rumble of vehicles were heard during the small hours. Though, conceivably, they were from Grandpa`s fleet, for he owned a transport company in nearby Blandford Forum.

In more recent years my suspicions about his activities had deepened; but it never became an issue where I wanted to find out.

*

He died at ninety five. Though, even when he became a nonagenarian, he was still full of vigour, his mind wonderfully active. I suppose it was only in the past few months of his life he started to slow, the years and his exploits catching up with him.

I poured more wine, and thought of the subtle but now obvious influence Grandpa Johns had had on my choice of career. He had steered me towards the Courtauld Institute of Art, and visions of my time there came to mind. Memories brought a wry smile to my lips. Though my fellow students and I worked hard at our chosen subjects, there was always room for creative entertainment. Most often pranks played on others: some lavish, some light-hearted, some mildly dangerous.

I vividly recall one occasion: to herald a forthcoming modern art exhibition, one of the official acts was to fly a colourful flag from the South Wing of Somerset House, overlooking the Embankment and the River Thames. Several of my friends and I painted a horrific female nude in bright colours, and drew lots to determine who would climb the domed roof on which the flagpole was located.

I drew the short straw.

From the ground it looked deceptively straight-forward. There was an iron ladder with a handrail over the roof to the base of the flagpole. It is not so easy at night, nor did I take into account the strength of the wind at that altitude. Neither, did I realise, until that moment, I suffered from vertigo. Hanging on tightly I inched my way to the base of the pole and tugged the flag from my anorak. Whereupon the wind caught it, the flag promptly unfurled and wrapped itself around me.

For several terrifying minutes I clung to the rail until the wind eased and my heart stopped pounding. How I managed to secure the flag to the rope and haul it up the mast I shall never know. When I got down my knees would not stop shaking.

Artifice

Artifice